Folk songs collected in King’s Lynn in January 1905, by Ralph Vaughan Williams

In April 2021 some of this material was included in a talk entitled ‘100 years of singing in a fishing community: King’s Lynn 1870-1970’ for The Folk Voice conference, organised by the Traditional Song Forum. In that talk, I compared the1905 findings of Vaughan Williams in King’s Lynn with songs found in Henry Flanders’ handwritten song book from the late nineteenth century, and recordings made in the mid twentieth century. You can see that 20 minute presentation here, on the Traditional Song Forum’s YouTube channel.

Foreword

This article concerns a visit by composer Ralph Vaughan Williams to King’s Lynn in north west Norfolk in 1905 and identifies the singers. Links to the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library online archive are given for each song.

This article supersedes my earlier writing on the EATMT website.

Anyone wishing to cite this original research should credit it to Katie Howson and cite this website as the source. © Katie Howson 2021

This is a long article, and is divided into several sections: 1. Introduction; 2. The singers and the songs, in which singers are listed in alphabetical order, first those whom Vaughan Williams found living in the North End, followed by those in the workhouse, together with links to their songs; 3. Other singers and songs; 4. Further Information.

1. Introduction

In the early twentieth century, there was huge interest amongst English composers and art musicians in the traditional folk songs still being sung, mainly in the countryside. However, unlike today, when we can easily access huge online repositories of folk tunes and lyrics, the composers of Edwardian times had little material to draw on and so many went out on field trips to find and note down ancient melodies from the older generation of farmhands, fishermen, washerwomen, innkeepers and domestic servants. The most famous of these composers was Ralph Vaughan Williams, who, in 1903 collected his first folk song from Charles Potiphar at Ingrave, near Brentwood in Essex. During the following decade, he collected nearly 800 folksongs, the vast majority noted down with pencil and paper whilst listening to the singers. The influence of the melodies he heard shaped many of his compositions such as the Norfolk Rhapsodies (1906), Fantasia on English Folk Songs (1910) and Lark Ascending (1920).

Vaughan Williams’ first folksong collecting trip was at the invitation of Georgiana and Florence Heatley, daughters of the Reverend Henry Davis Heatley of Ingrave in Essex. In subsequent years he revisited this area and began to investigate, through a circle of like-minded friends and contacts, singers and songs in many areas of England. He returned to East Anglia on a number of occasions, collecting songs in north Norfolk, Cambridgeshire and Suffolk.

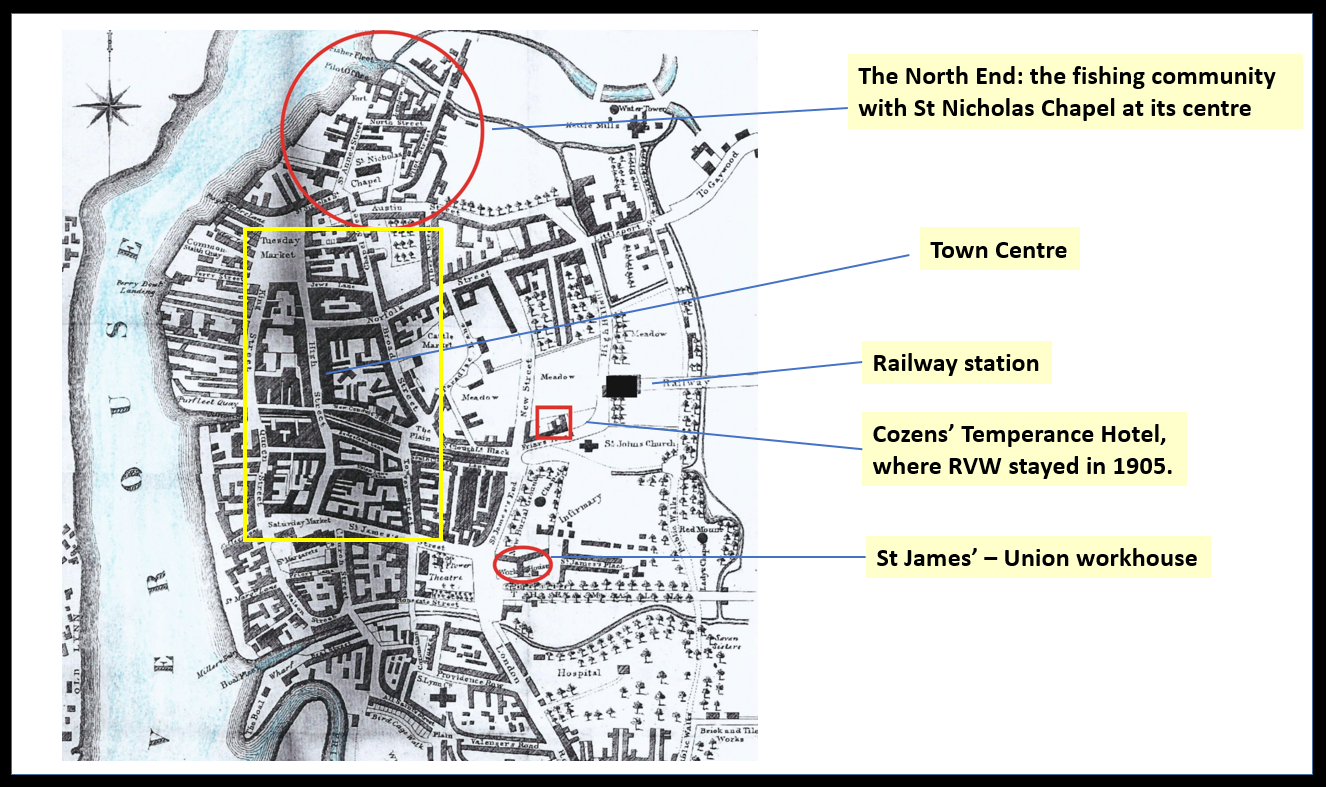

The trip to King’s Lynn, January 1905

Early in January 1905, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams set out on a folk song collecting trip to north west Norfolk, starting in Tilney All Saints, to the west of Kings Lynn on Saturday 7th. Over that weekend he recorded songs from a gardener and church sexton, John Whitby, and in nearby Tilney St Lawrence, some dance tunes from fiddle player Stephen Poll. He then headed in to the town of Kings Lynn, to the tight-knit fishing community of the North End and also to the workhouse. Taking a break to travel east along the coast to Sheringham on the Wednesday, he stayed until Sunday 15th January and recorded over seventy songs. He returned for a day on Saturday 1st September 1906, again visiting both the North End and the workhouse.

Vaughan Williams noted down the melodies he heard with a pencil and music manuscript paper. He was careful to note melodic variations, and the title of the piece and who sang it. If it was a song he had not come across before, he would write down all the words, but if it was a familiar set of lyrics to him, he did not always write them down. It would have been a slow process to transcribe the music as sung to him by these fishermen and labourers, and Vaughan Williams’ interest was always primarily the melody. Unusually for a man of his status in those class-conscious days, he was quite happy to visit pubs to hear singers, but on this visit to King’s Lynn he seems to have only visited people in their homes, which enabled him to note songs from several women, who, in those days, rarely visited pubs.

For some years there was a story that he had collected songs in the pubs of King’s Lynn and one pub even had a plaque stating this as fact, but there is actually no evidence for him visiting any pubs in the town, and my research has unearthed people a younger generation who were singing in pubs in 1905, whom Vaughan Williams did not encounter. Any statement about him visiting the Tilden Smith pub is a backward projection of facts from the 1950s to the 1900s – which us researchers are all now agreed on – so don’t believe it if you read it elsewhere – it’s old news or fake news! Vaughan Williams was in the company of a clergyman for much of his visit, which would also have made a pub visit unlikely. You can read a short, relevant, article about The Tilden Smith here.

It was through this clergyman, the Reverend Alfred Huddle, curate of the fishermen’s church at the heart of the fishing community, St Nicholas Chapel, that Vaughan Williams was first introduced to singers in the North End of King’s Lynn. When Vaughan Williams gave a lecture in Norwich in 1910, the local newspaper (Eastern Daily Press, 17 September 1910) reported his comments about the King’s Lynn trip thus:

“He had had the good luck to find a good many sailor songs in Norfolk, chiefly King’s Lynn. These he came upon by pure chance. After visiting the country places around, and getting nothing, he was about leave the district in despair, when a curate in King’s Lynn [Ed: Rev. Huddle] asked him if would like to see the fishing people in the North Town. He said he should, and was taken into some of the worst slums he had ever been into in his life. He was there very forcibly reminded of the fact that the appeal of the folk-song was to the ear and not to the nose. (Laughter.) Instead of going away he stayed a week. He met some very hard-working and very poor fishermen, and they sang to him when they could get away from their work. He noted down 76 genuine ballads in one week. (Applause.).”

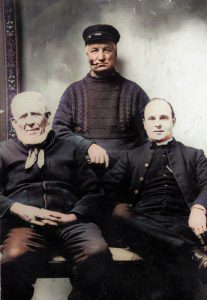

Amongst the fishermen, Vaughan Williams was introduced to James “Duggie” Carter (back right in this photo), who sang The Captain’s Apprentice, (see below) and Joe Anderson (left in the photo), who sang Young Henry the Poacher, which Vaughan Williams used in his English Hymnal in 1906, as the tune for a poem written by G.K. Chesterton. The hymn, no. 562, bears the name King’s Lynn. Both Carter and Anderson were known well by the curate of St Nicholas’ Chapel, the Reverend Alfred Huddle (right in the photo) and would have sung in the Chapel regularly, as well as in more secular settings.

Amongst the fishermen, Vaughan Williams was introduced to James “Duggie” Carter (back right in this photo), who sang The Captain’s Apprentice, (see below) and Joe Anderson (left in the photo), who sang Young Henry the Poacher, which Vaughan Williams used in his English Hymnal in 1906, as the tune for a poem written by G.K. Chesterton. The hymn, no. 562, bears the name King’s Lynn. Both Carter and Anderson were known well by the curate of St Nicholas’ Chapel, the Reverend Alfred Huddle (right in the photo) and would have sung in the Chapel regularly, as well as in more secular settings.

Vaughan Williams noted songs from a number of other men in the area, and also from several women. The North End women were also economically involved in life at sea through such activities as fish-hawking, net-mending or knitting the distinctive fishermen’s ganseys for husbands, brothers and fathers. This was of course in addition to bringing up large numbers of children, keeping the tiny cottages spotless and feeding their children and menfolk.

A letter from Vaughan Williams to Ralph Wedgwood tells us that he stayed at the Cozen’s Temperance Hotel (see map, above) which was just a few minutes’ walk from the North End fishing community, but a few minutes’ walk in the opposite direction brought him to St James’ Union workhouse, where he also collected a number of songs on three visits during his week in the town.

2. The singers and the songs

Over a hundred years later, we are in the privileged position of being able to look directly at Vaughan Williams’ transcriptions and notes from the comfort of our own homes, as these have all been digitised and are available online at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library Online website. Direct links to each song are to be found within the text about each singer below.

Having carried out extensive genealogical research, I have now positively identified most of the singers from Vaughan Williams’ two trips to King’s Lynn in 1905/6, some of whom were named only by their surname in the song collector’s notes. If anyone has any further information or photographs, I would be very pleased to hear from them – just drop me an email.

The North End

Joe Anderson (1833-1906)

Born in 1833, son of a fisherman, Joe Anderson was born and brought up in the North End. He also went into fishing, and in 1855 married Martha Allen, with whom he had a son, also called Joe. By this time he had diversified his income by becoming licensee of the Black Joke, on North Street as well as continuing to be a fisherman. Martha died in 1861 and Anderson soon married Mary Ann Starling in 1862. Together they took on the Norfolk Arms, also on North Street, which they ran from 1864-1869, and had three daughters. A newspaper report from 1877 reveals that he sailed “by shares” with George Anderson and William Hendry. They had been accused of catching mussels in the close season by the corporation’s water bailiff, Sebastian Terelinck, who had previously been licensee of the Earl of Richmond on Pilot St – hence George Anderson’s remark: “When Terelinck asked them for their names, they inquired if he did not know them.” Joe and his family moved round the corner to St Ann’s Street, then North Place, where Mary Ann died in 1897. His last move was to Churchman’s Yard, where he lived with his daughter Roseanna until her marriage in May 1905, when she and her husband moved out and Anderson lived out his last year in his own home. He was baptised, married and buried in St Nicholas Chapel, where he was apparently also confirmed as an adult.

Joe Anderson sang: Young Henry the Poacher, Yorkshire Farmer, John Reilly, Basket of Eggs, Erin’s Lovely Home, Sheffield Apprentice, The Bold Robber, Bold Young Sailor, The Nobleman & the Thresherman, Bold Princess Royal, Young Indian Lass, As I was a-walking ( Young Sailor Cut Down in his Prime)

Mr Bayley (dates not known)

Nobody has been able to positively identify this singer, about whom Vaughan Williams noted he was a fisherman and “had gained a prize for singing this song [Ward the Pirate] at a cheapjack’s singing match.”

Vaughan Williams spells his name this way several times, but there’s no-one with this spelling “Bayley” in the official records, so it must have been Bailey. It’s possible he was a relative of Lol Benefer (née Bailey) – she had an uncle Jacob, who was close to his brother William, Lol’s father (see below). This possibility is strengthened by the fact Jacob’s wife was Elizabeth, and Vaughan Williams also noted songs from “Elizabeth” (no surname) on Wednesday 11th January. The other possibility is that Mr Bailey was friends with, or even related to, James “Duggie” Carter, as Vaughan Williams had the same songs from the two of them on the Monday.

Mr. Bayley sang: I Went to Betsy, The Blacksmith, Ward the Pirate, the last two together with (or had variants) James “Duggie” Carter.

Harriet Ann “Lol” Benefer (1864-1926)

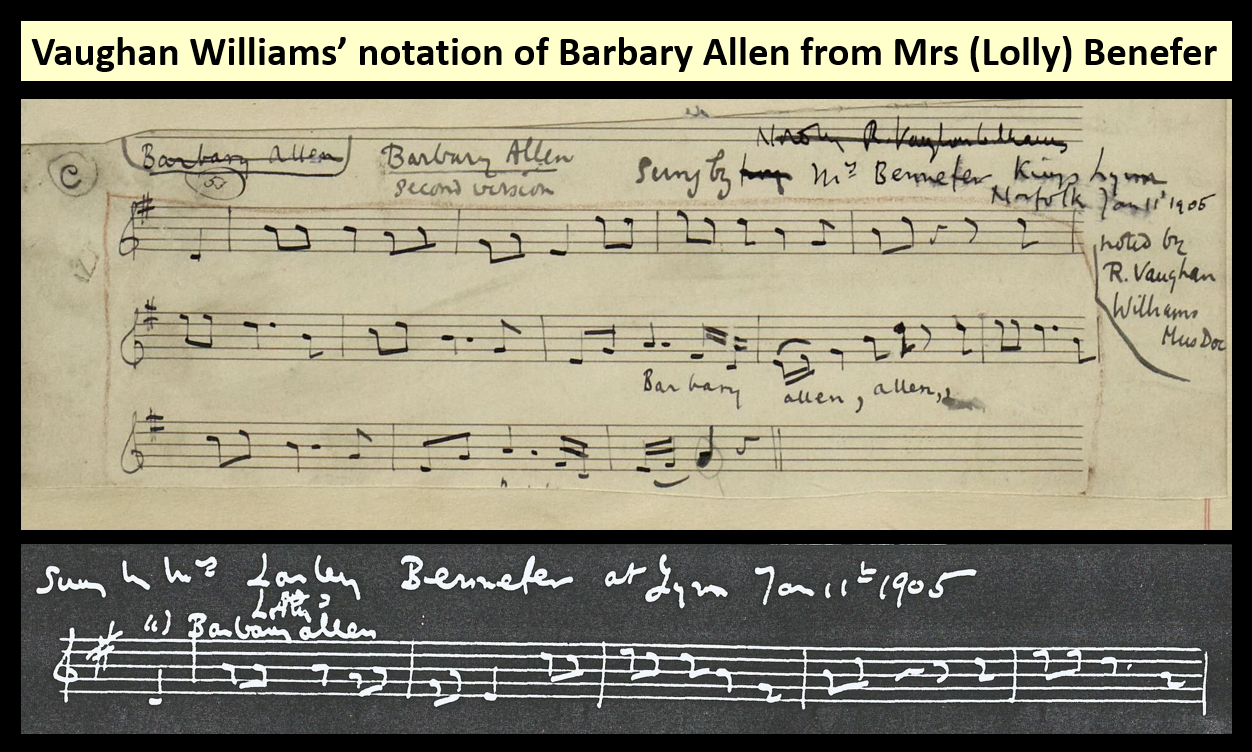

Vaughan Williams noted two songs from a Mrs. Benefer, and in one of his notebooks he had made an attempt at her first name, which I interpreted as “Lesley” for many years, although this didn’t feel a very likely name. The lightbulb moment came nearly ten years after first looking at that manuscript, when, on a local history web group, I came across the name Lol Benefer, and realised that the name Vaughan Williams had tried to spell was Lolley/Larley!

Vaughan Williams noted two songs from a Mrs. Benefer, and in one of his notebooks he had made an attempt at her first name, which I interpreted as “Lesley” for many years, although this didn’t feel a very likely name. The lightbulb moment came nearly ten years after first looking at that manuscript, when, on a local history web group, I came across the name Lol Benefer, and realised that the name Vaughan Williams had tried to spell was Lolley/Larley!

“Lol” was born Harriet Ann Bailey in 1864, daughter of William and Mary Ann Bailey. William was a fisherman and the family lived in a yard off North Street, where in 1882, a tragedy which developed from a domestic row with a neighbour was to have a huge impact on their lives. The row appeared to be about young children from the two families playing together in the communal yard and Lol, her older sister and both parents assaulted a young neighbour, James Stannard, who died a fortnight later. There were questions about whether the supposedly quite minor attack, involving a child’s shoe, was actually the cause of death, but in the end, the family were all sentenced to imprisonment and sent to Norwich Gaol for periods of eight to twelve months. Whilst in prison, Lol gave birth to an illegitimate son. Soon after he release she struck up a relationship with fisherman Henry Benefer, with whom she had a son, Tom, and subsequently she and Henry were married and went on to have a very large family. When Vaughan Williams visited in 1905, she was aged thirty-nine – much younger than his average singer – and had three children under the age of four, so it would have been quite a challenge to find somewhere quiet to note her songs. By the early 1900s the family was living in Whitening Yard, and later moved onto North Street itself, where both she and her husband died – Henry in 1925 and Lol in 1926.

Lol sang: Barbary Allen and The Farmer’s Daughter – more usually known as The Banks of the Sweet Dundee.

Lol was not the only one in her family to sing. Her eldest daughter Jessie’s son, Eric, is said to know some of the old songs. Her second daughter, another Harriet, married George Smith, who was known as ‘Bussle’, as was his father and subsequently his son, and Harriet’s husband and father-in-law were both singers. Lol’s younger sister Naomi had a daughter called Lottie who was adopted at an early age by fisherman and singer James “Duggie” Carter – see below. Her second son, Tom “Boots” Benefer, another of the North End’s well-known inhabitants, also sang. He was one of the men who sang on a radio programme made by writer John Seymour, recorded in the Tilden Smith pub in the North End on 4th July 1955 and broadcast in a series about a journey Seymour and his young family made around England in a Dutch sailing barge: The Voyages of Jenny III. But that is a story for another day.

There is more about Lol’s life story here: http://unsunghistories.info/the-other-mrs-benefer

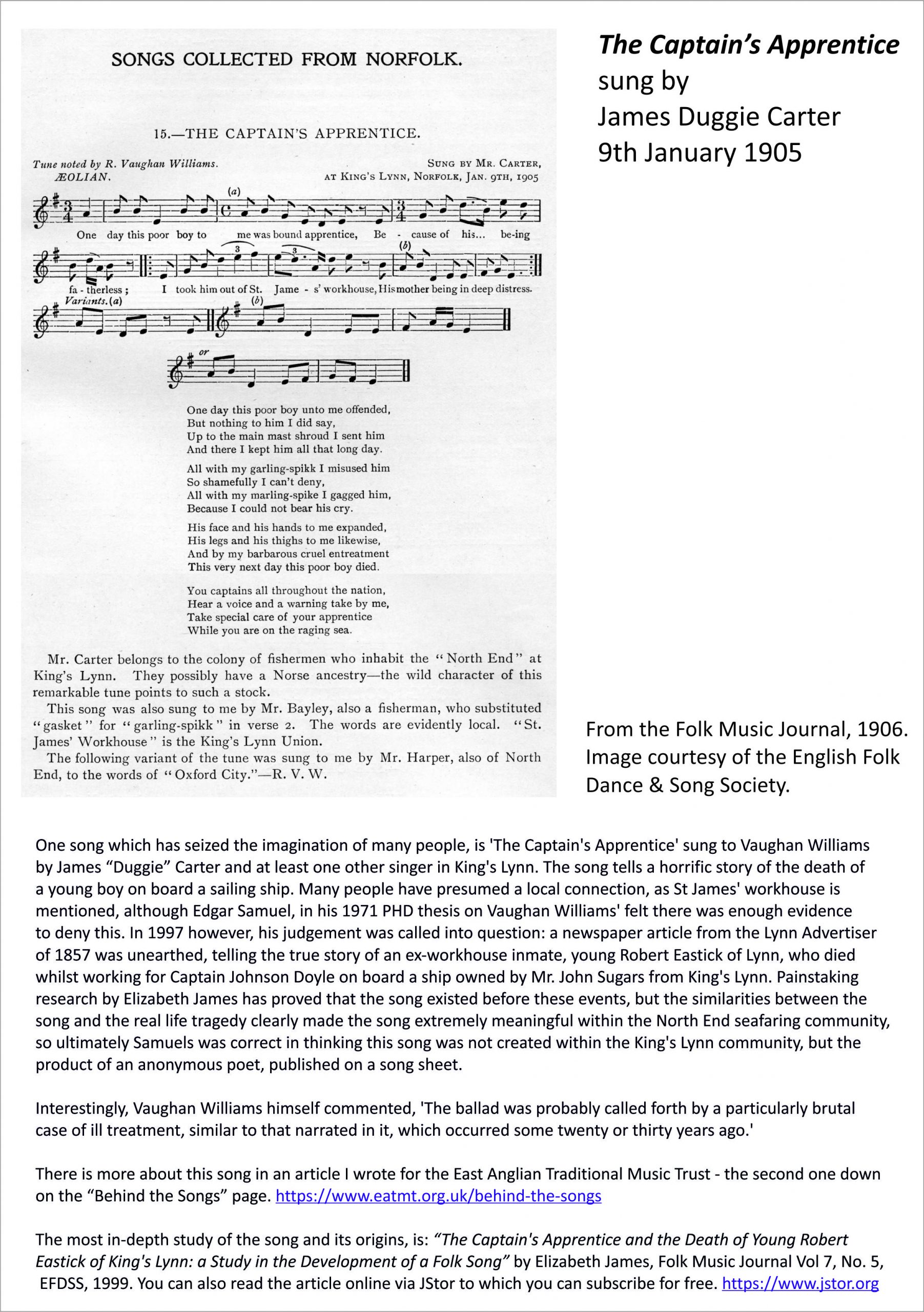

James Edward Bouch “Duggie” Carter (1844-1915)

James “Duggie” Carter was born in 1844, son of a fisherman, and spent his young life in a cottage in one of the yards off North Street. In 1865 he married Alice Harper, whose father was a tailor on St Ann’s Street, and Duggie and they moved to Hanover Yard, off St Ann’s Street where they soon began a family. By 1881 they were in Watson’s Yard, off North Street, where they remained for many years.

1904 was a tough year for him, with his wife and mother both dying. He was evidently still in the North End in January 1905, when Vaughan Williams visited, but he then gave up fishing and worked on the docks, and moved in with his adoptive daughter Lottie, living in the Victorian terraced streets just north of the old North End. Lottie was actually a niece of singer Lol Benefer, and it’s not clear how they were related to Duggie & Alice, but they did a good job of bringing her up as, when interviewed in 1976, she had clear memories of him singing over 60 years previously. Also involved in that interview was a granddaughter of Duggie, Florrie Reid, who recalled that, “when the new Eastern Channel, which changed the course of the Ouse between Lynn and the sea, was opened in 1853, James Carter was the first man down it in a boat, when the water gushed through. ‘They said it was suicide’ said Mrs Reid […] Her grandfather was only a young man then, of course, and his son [Tom] told his children the story of grandfather’s escapade, which fortunately he survived.”

This quote is taken from an article by Elizabeth James, published in the magazine of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, English Dance & Song: “James Carter, Fisherman of King’s Lynn, the man who sang The Captain’s Apprentice to Vaughan Williams”. (Vol 39, no.1, 1977.)

Duggie Carter sang The Deeds of Napoleon, The Captain’s Apprentice, Ward the Pirate, The Dragoon and the Lady, The Blacksmith, The Golden Glove and A Sailor was Riding Along for Vaughan Williams. In 1976 Elizabeth James interviewed his daughters, who also recalled him singing The Dark-Eyed Sailor.

Thomas Donger (1843-1915)

Thomas Donger was one of the few singers from the North End who had not been born into the tight-knit community, in fact although living and working in the town for at least thirty years, he had only recently moved into Begley’s Yard, off North St. Whether this represented an upwards or downwards trajectory in life can’t be told at this point in time, but he ran his own business, making sails and marquees, and hiring out the latter. A listing in the 1912 Kelly’s Directory gives his premises address as Tuesday Market Place, and includes tarpaulin, sack and bag manufacturing under his activities.

Donger was born in Hoddesdon, Herts, and for once, Vaughan Williams’ notes may tell us something that has not been revealed through a search in the formal records: that he had been a sailor. This would make absolute sense in that he is one of the few singers to have sung any shanties, suggesting he had been in the merchant navy. This may also be why he’s not found on the 1871 census, shortly after his marriage to Charlotte Armes, who is living with her parents in Walpole St Andrew.

His first premises and home in King’s Lynn were near the town centre, where the family also tried their hand at running the Beaconsfield Restaurant for a few months in 1888. His two sons, Thomas and Horace followed him into the sail-making business. In 1915, during the First World war, his son Thomas died at sea in Gallipoli, and “our” Thomas died just a couple of months later. By this point the family seem to have left the North End again, although Thomas is buried, like so many of Vaughan Williams’ singers in St Nicholas’ Chapel.

Thomas Donger sang: The Hills of Caledonia, Pat Reilly, Glencoe, The Convict, Spanish Ladies, Come all you Young Sailors, Come all you Gallant Poachers, The Banks of Claudy, Erin’s Lovely Home and two shanties, Heave Away and Shenandoah. Vaughan Williams evidently found his singing of interest, as he was one of the few people he called on during a short visit back to King’s Lynn in September 1906.

William James Harper (1830-1906)

William Harper’s family history is quite complex. He was born the son of a labourer – his parents married when they realised his mother was expecting a baby, aged 18, and his father died less than four years later. His mother remarried after a couple of years, when William was just six, and in the 1841 census I found him living with his grandparents and the daughter of his new stepfather by his first wife. His mother and stepfather meanwhile were just round the corner with a one-year old daughter. By 1851 the various branches of the family were under one roof, with the addition of a new stepbrother, Tom Senter, who would turn out to be a musician himself, playing the piccolo and concertina.

William followed in the footsteps of his stepfather and became a fisherman, and in 1863 he married Sarah Anne Thomas; they already had a son together, James, born in 1861. The family lived in a succession of yards around the North End – Chapel Yard, then True’s Yard (where the museum now is) and then Watson’s Yard, where he was neighbour of another of Vaughan Williams’ singers, James Duggie Carter. William and Sarah Harper only had the one child, but in their sixties they took on another youngster, Frederick Simmons – perhaps a great-nephew. Late in 1906 William Harper died and was buried in St Nicholas churchyard. It seems he may have ended his days in the workhouse, as he appears in their 1906 records. Vaughan Williams paid a brief second visit here on 1st September but didn’t meet / collect any songs from Mr. Harper.

William Harper sang: Fair Flora, Just as the Tide was Flowing, Oxford City, Poor Mary, Captain Markee (Henry Martin), Edward Jorgen, Betsy and William, My Bonny Boy and Paul Jones (The American Frigate).

Vaughan Williams wrote, on the page where he noted Poor Mary – “Mr H. said, ‘I could take it up and down again just as you do in the music’ (i.e. when he was young)”, and against Betsy and William he noted that “Harper’s brother said that the old songs were ‘wonderful mellow’.” This could imply that Vaughan Williams met his brother too – the only brother he had was in fact a half-brother, Tom Senter, the musician, but Vaughan Williams doesn’t mention him directly, so it could just be a quote from William Harper himself.

Betty Howard

I’ve not been able to positively identify a Betty Howard so far. Vaughan Williams noted she was aged about seventy, but in other cases his guesses at the ages of his singers have not been very accurate, so this is not an infallible guide.

Betty Howard sang three songs: Ratcliffe Highway, The Sheffield Apprentice and Homeward Bound (Our Anchor’s Weigh’d).

The last song named is an unusual item to find in a woman’s repertoire, as it is a sea shanty which was used on sailing ships as a way of keeping teams of men working in time. It may indicate that Betty Howard’s husband was a mariner rather than a fisherman.

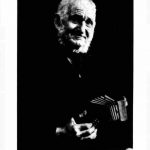

Mr Smith

Vaughan Williams gave us no clues as to who this man might be, and as might be expected, there are several Smith around in the North End. However, one stands out as being the most likely person for him to meet. George “Bussle” Smith was father-in-law to one of Lol Benefer’s daughters and lived close by. His son, “Young Bussle” told folksong collectors later in the twentieth century that he had learned songs from his father, who sang at home. So it seems quite probable that Vaughan Williams’ “Mr Smith” was George William “Old Bussle” Smith (1854-1939) a fisherman who was living in North End Yard in the 1900s, but moved out of the North End to more comfortable council housing when the yards were demolished in a slum clearance scheme of the 1930s.

Mr Smith sang the sea song Bold Princess Royal to Vaughan Williams, but if my surmisings are accurate, he probably also sang lighter material such as Golden Slippers and Rarum Tearum Fisherman (also known as Dogger Bank), which were staples of “Young Bussle”’s family later in the twentieth century.

Elizabeth

Elizabeth sang two songs: It’s of a Shopkeeper and The Three Butchers. With no further clues as to her name, she cannot conclusively be identified. Looking at the circumstances of the visit, I would hazard a guess that she was related to Lol Benefer. My best guess is her aunt Elizabeth, married to her father’s brother Jacob Bailey, but there’s no proof!

The workhouse

The original workhouse in Lynn incorporated a thirteenth century chapel of St James, and was called after that. In 1854 the central clock tower collapsed, killing two people. The chance was taken to build on a new site, which opened in 1856 and was further updated in the 1880s. As with so many old workhouses, in the course of the twentieth century it became a hospital, which closed in 1985. Some of the buildings remain, and some partial records are archived in the Norfolk Record Office, which provided me with further clues to identify some of the singers Vaughan Williams met there in 1905. Alan Helsdon has written more about Vaughan Williams; visits to the workhouse (see Further Information section towards the end of this article) and there is more information about the workhouse itself here.

Interestingly, none of these singers were from the North End, most were labourers on the docks or mariners of some sort, but they had lived in South or central Lynn, where family and community support systems were perhaps not so strong.

John Thomas Chesson (1840-1913)

Vaughan Williams noted him simply as “Mr Chesson” but workhouse records have revealed him as John Thomas Chesson.

John Chesson went to sea at early age: in the 1860s, he is described as a mariner, and the fact he’s not found in the 1851 census suggests he was away at sea as a cabin boy, aged eleven. Such was the case in the 1871 census as well, by which time he had married Anna Roberts who was at home with their young children. As his family grew, John took a land job as a porter in the docks and the family continued to live in South Lynn until his wife died in 1895. He then moved in with one of his daughters, but was admitted to the workhouse in July 1904. He left in April 1905, but by the time of the 1911 census he was back in the workhouse. He died in 1913, when his address was given as St Ann’s Fort – in the North End, however, he was buried in All Saints Churchyard, not St Nicholas.

Mr Chesson sang two songs to Vaughan Williams: Erin’s Lovely Home and The Raven’s Feather (The Cruel Father).

George Cooper

This is most likely to be George Cooper, who died, aged 73, in the workhouse in March 1906, but I can find no further information on this man. Another George Cooper died in April 1917 in the workhouse, aged 77. This George William Cooper had been a labourer living in Lynn all his life, but in 1901 and 1911 he was living with his son (also George William, single) so it doesn’t seem that likely he would have been in the workhouse in 1905 when Vaughan Williams visited, so the jury is still out on who exactly this man was.

Mr Cooper sang one song, The Irish Girl, to Vaughan Williams.

Charles Robert Crisp (1842-1921)

Vaughan Williams’ handwriting had for years been misread as naming this man “Mr Crist”, whereas comparing his letter formation elsewhere, it is clearly “Crisp”. Workhouse records have revealed he was Charles Crisp, b. 1842.

However we have few hard facts about Crisp. He may have been born in Gaywood, near Lynn, in 1842, and he was at sea by the mid 1850s. In 1861 he turns up in the census as an ordinary seaman on board the Ceres, moored in Yarmouth Roads. The Ceres was a Brigg employed in the coal trade and they had been in Sunderland a week earlier. Mercantile Navy records reveal him as an able seaman on the Dare in 1866, and his previous ship was the Trowbridge. He’s not found in any census or other documentation in England until 1901, but he does appear to have joined the US army in 1871! The records tell us that he enlisted on 14th March for three years general service as a seaman, in Boston, but already had five years previous service. Amongst the fifteen others on the page, only one other Englishman, John Healy from Liverpool, four Irish, a Prussian and the rest are American. Crisp was aged 34, with a dark complexion.

There is no sign of any family (although he is later described as a widower), but he evidently returned to Lynn in later life, when he really fell on hard times. He had at least four spells in the workhouse: in the 1901 census he was described as a pauper; he was admitted again in September 1904 and stayed until just after Vaughan Williams visit in January 1905; he was back again from July 1906 to 13 Sept 1906 – just in time for Vaughan Williams’ second visit – and was in once more at the time of the 1911 census. There is an entry in 1906 in the workhouse punishment book recording that Crisp had been let out on leave with two coats and had sold one and tried to sell the other. A newspaper report from 1918 about a Robert Charles Crisp is consistent with this scenario – Crisp was accused of stealing a coat and appears to have been living on the streets. This was from the Peterborough area, and this man seems to have died in 1921, at Witchford, also in Cambridgeshire.

Mr Crisp sang: Dream of Napoleon, Bold Princess Royal, Loss of the Ramillies, Hills of Caledonia, The Cumberland’s Crew, Maid of Australia and Spanish Ladies.

George Elmer (1839-1923)

Again, Vaughan Williams noted his name as simply “Mr Elmer” but workhouse records have helped to identify him as George Elmer. Documentary evidence is scant and inconsistent, but it seems he was born in 1839, son of a labourer, who moved his growing family to King’s Lynn in the early 1840s. They lived in the dock area, and in 1863 George married Mary-Ann Hammond, known as Ellen. The couple had no children, George worked as an “excavator” – I think this must be a navvie, or labourer, digging foundations. From at least 1901, he was in and out of the workhouse regularly until at least 1911, including over the winter of 1904/5, when Vaughan Williams came looking for songs. Mr Elmer was also there when Vaughan Williams came back on 1st September 1906.

A list in the Lynn Advertiser on 28 December 1923 of long-lived Lynn residents who died that year includes George Elmer, aged 84.

Mr Elmer sang: It’s of an Old Lord, Lord Bateman, The Fourteenth Day of February (not Bold Princess Royal), Kilkenny and The Bold Robber.

Robert Leatherday (1842-1918)

Vaughan Williams gave only his surname (as he did with all the workhouse residents) and noted he was a sailor. This has turned out to be a bit of a red herring. Many hours of detective work have at last allowed a positive identification of this man as Robert Leatherday. He was brought up by his widowed mother in South Lynn, married Sarah Anne Clackold in 1867 and they moved to Cambridge for a brief period, where he is recorded on the 1861 census working as a brickmaker. He moved back to his home town, where he worked as a labourer, living apart from Sarah, in a series of lodgings in South Lynn. He was admitted to the workhouse in July 1901, and was there for both of Vaughan Williams’ visits in 1905 and 1906, and also there on the census night in 1911, where he was described as a former builder’s labourer and a widower. He died in March 1918, in the workhouse infirmary, where the cause of death was recorded as epilepsy and bronchitis. There’s no sign of him ever having been a sailor, and although his older brother did, he died in 1885, and no other Leatherdays fit the age profile.

Mr Leatherday sang: On Board a ’98, Come People All (Spurn Point), Creeping Jane, Robin’s Petition, The Three Butchers and Spanish Ladies.

Christopher Woods (1826-1906)

Again, Vaughan Williams just gave us his surname, and the detail that he had been a sailor – in this case, he had accurate information! The workhouse records tell us that he was Christopher Woods, who was admitted in June 1904 and died there in September 1906, aged 80.

Christopher Woods was born and brought up in the centre of town, with his family running a bakers and confectioners business. He went to sea and in 1854 married the daughter of a ship’s master. He continued working in the merchant navy until at least 1891, bringing up his family in the same area of the town, not far from the docks. His wife died in 1898 and so by the time he entered the workhouse in 1904, he was a widower in his late seventies. From family members I understand he was buried in Hardwick Road cemetery on 15th September 1906.

Mr Woods sang just one song to Vaughan Williams, Napoleon’s Farewell in January 1905 and was evidently too unwell by his second visit on 1st September 1906 to sing anything more.

3. Other singers and songs in King’s Lynn

The ones that (nearly) got away

There were undoubtedly other singers around in 1905 in a town the size of King’s Lynn, and I have evidence for a good half-a-dozen or so, most of whom were younger men singing in the pubs, and with an indication that they were singing different songs.

Just to give you an idea, one singer in his thirties won a singing contest in 1905 with his performance of Lord Bateman – the winner was the person with the longest song! Also around at that time was Tom Senter (pictured, left), who was half-brother to one of Vaughan Williams’ singers, William Harper. Tom is said to have been a singer, but was certainly also a musician as there are photographs of him playing both the concertina and the piccolo.

Just to give you an idea, one singer in his thirties won a singing contest in 1905 with his performance of Lord Bateman – the winner was the person with the longest song! Also around at that time was Tom Senter (pictured, left), who was half-brother to one of Vaughan Williams’ singers, William Harper. Tom is said to have been a singer, but was certainly also a musician as there are photographs of him playing both the concertina and the piccolo.

An article entitled The fishermen that got away is now on my Unsung Histories blog.

Henry Flanders song book

Some years ago I came across a mention of a handwritten nineteenth century songbook from King’s Lynn, which is in the keeping of one of his great-granddaughters in New Zealand, herself now in her nineties. The book contains 150 songs written out, a real mixture of parlour songs, sea songs, folk songs and music hall material which had belonged to Henry Flanders, a fisherman and fish dealer living in the North End. He was born in 1842, making him a contemporary of some of the people who sang to Vaughan Williams, but he died, aged only 48, in 1890.

Some years ago I came across a mention of a handwritten nineteenth century songbook from King’s Lynn, which is in the keeping of one of his great-granddaughters in New Zealand, herself now in her nineties. The book contains 150 songs written out, a real mixture of parlour songs, sea songs, folk songs and music hall material which had belonged to Henry Flanders, a fisherman and fish dealer living in the North End. He was born in 1842, making him a contemporary of some of the people who sang to Vaughan Williams, but he died, aged only 48, in 1890.

His collection of songs is thus unmediated by the folk song collector and might prove indicative of the wider repertoire of “folk” singers. A longer article about Flanders and his songs is on my Unsung Histories blog (link coming soon!)

The company of the Tilden Smith and other singers from 1955 onwards

In 1955, the Lynn News and Advertiser of 8th July carried a story, written in a very lively style, about a radio recording made in the Tilden Smith pub which included songs from Charlie Fysh (left, with his wife, Sarah), Tom Benefer, George Smith and Bob Chase.

In 1955, the Lynn News and Advertiser of 8th July carried a story, written in a very lively style, about a radio recording made in the Tilden Smith pub which included songs from Charlie Fysh (left, with his wife, Sarah), Tom Benefer, George Smith and Bob Chase.

The programme turned out to be the first in a series called “The Voyages of Jenny III” made by writer and broadcaster John Seymour (later of “Self-Sufficiency” fame). Unfortunately no recordings exist now, but the newspaper report allows the reader to imagine the scene vividly.

In the mid 1960s, oral history recordings made by Mike Herring and the Norwich Tape Recording Society revealed that there were still traditional singers amongst the older generation of fishermen, including “Young Bussle” Smith (who turned out to be the very same George Smith from the 1955 radio programme) and John Slinger Wood.

An article entitled The self sufficient singers of the Tilden Smith is now on my Unsung Histories blog and another The Herring Singers will be published there shortly.

4. Further information

Alan Helsdon has done a marvellous job of recreating Vaughan Williams’ visit to King’s Lynn (and also Tilney and Sheringham) in minute detail, which is available as a kind of E-Book with sound files, by buying a CD-Rom – here’s the link: https://mainlynorfolk.info/folk/books/vaughanwilliamsinnorfolk.html

Here is the link again for Elizabeth James’ article – after you’ve registered, just type in Elizabeth + James + King’s + Lynn into the search box and you will be able to read the whole article. https://www.jstor.org/

Liz James and co-author Jill Bennett are working on a new book about Vaughan Williams in King’s Lynn, and Caroline Davison is writing “The Captain’s Apprentice: Biography of a Song” http://www.carolinedavison.co.uk/current-project

Both books are due out in 2022, the 150th anniversary of Vaughan Williams’ birth.

All my other articles about King’s Lynn are to be found on my other website: http://unsunghistories.info

Afterword

Thanks to Elizabeth James, the True’s Yard Fisherfolk Museum and the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library of the English Folk Dance & Song Society.

Thanks to Elizabeth James, the True’s Yard Fisherfolk Museum and the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library of the English Folk Dance & Song Society.

This iconic image of “Old Bussle” Smith is from the True’s Yard Museum archives, and may well be the “Mr Smith” who sang to Vaughan Williams in 1905!

My research into Vaughan Williams and Butterworth’s folk song collecting in Southwold, on the Suffolk coast in October 1910, and around Diss in South Norfolk in 1911 has also been updated and is now on this site – just follow the links. Again, the information on the EATMT site is now superseded by the more recent versions published here.

© Katie Howson 2021