Folk songs collected around Southwold on the Suffolk coast in 1910, by Ralph Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth

In March 2021 I presented a different take on this material in a talk called ‘Up from the Sea’, looking specifically at sea songs sung in Southwold, and the artistic and musical visitors there throughout the course of the 20th century. You can see this presentation on the Traditional Song Forum’s Youtube channel.

Foreword

This article traces a visit by composers Ralph Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth to the Diss area in south Norfolk and identifies the singers and locations. Links to the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library online archive are given for each song.

This article supersedes my earlier writing on the EATMT website as it includes more information about George Butterworth, due to my involvement in the film “All My Life’s Buried Here’ by Hajdukino Productions, released in January 2019. This film is now available on DVD and can be bought by following the previous link.

Anyone wishing to cite this original research should credit it to Katie Howson and cite this website as the source. © Katie Howson 2022

Introduction

In the early twentieth century, there was huge interest amongst English composers and art musicians in the traditional folk songs still being sung in the countryside. However, unlike today, when we can easily access huge online repositories of folk tunes and lyrics, the composers of Edwardian times had little material to draw on and so many went out on field trips to find and note down ancient melodies from the older generation of farmhands, fishermen, washerwomen, innkeepers and domestic servants. The most famous of these composers was Ralph Vaughan Williams, who, in 1903 collected his first folk song from Charles Potiphar at Ingrave, near Brentwood in Essex. During the following decade, he collected nearly 800 folksongs, the vast majority noted down with pencil and paper whilst listening to the singers. The influence of the melodies he heard shaped many of his compositions such as the Norfolk Rhapsodies (1906), Fantasia on English Folk Songs (1910) and Lark Ascending (1920).

Vaughan Williams’ first folksong collecting trip was at the invitation of Georgiana and Florence Heatley, daughters of the Reverend Henry Davis Heatley of Ingrave in Essex. In subsequent years he revisited this area and began to investigate, through a circle of like-minded friends and contacts, singers and songs in many areas of England. He returned to East Anglia on a number of occasions, collecting songs in north Norfolk, Cambridgeshire and south Suffolk. In April 1910 he and George Butterworth teamed up for a successful song collecting trip in the Norfolk Broads and this was followed by further trips together to the Suffolk coast in October 1910 and south Norfolk in December 1911.

Butterworth himself often worked in partnership with other song collectors including Francis Jekyll (nephew of the garden designer Gertrude Jekyll) and the two of them had made many trips to Sussex together from 1906 onwards, on the trail of old folk songs. Butterworth was also a fine dancer and collected Morris dances along with Cecil Sharp. He was killed during the Battle of the Somme at a young age, but works such as The Banks of Green Willow (1913) show what a talented composer he was.

From the standpoint of the early twenty first century, we could wish that the Edwardian song collectors had taken a more sociological, or even anthropological approach, as they rarely gave details beyond the singer’s name and location.

The trip to Southwold, October 1910

On Monday 24th October 1910 Butterworth and Vaughan Williams went to Shadingfield to visit a Mrs Keble before carrying on to Southwold itself, where they stayed overnight, having probably travelled up from London by train with their bicycles. Here they noted down thirteen songs (not eleven as previously noted) from three brothers, William, Robert and Ben Hurr.

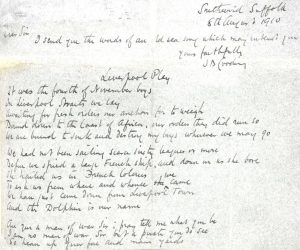

Until recently, the only known contact Vaughan Williams had in Southwold was a gentleman called Jonathan Gooding who had sent Vaughan Williams the words to a ‘sea song’ in a letter in August 1910 (see left). Gooding and his brother Donald had quite a substantial house at 49 High Street, and they evidently knew the Hurr family, who were the focal point for the visit, as Donald had collected some smuggling tales and ghost stories from the singers’ father, William Hurr in 1903. However, more recent findings suggest that a much closer acquaintance of Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw, was already aware of the town as a fruitful hunting ground for folk songs. Shaw and Vaughan Williams were lifelong friends, having known each other since the late 1890s when they both attended the Royal College of Music, and they subsequently collaborated on the ‘English Carol Book’ and numerous editions of ‘Songs of Praise’. Although born in London, Shaw had spent long periods in Southwold as a child, and continued to visit regularly in adult life, finally moving there permanently in the 1940s with his wife Joan Lindley Cobbold, whose family were from Bramford in Suffolk. In his autobiography, ‘Up to Now’, Shaw wrote of George Hurr, who used to take him fishing:

“George taught me to swim and to smoke. (I learned to smoke with shag tobacco, and still often enjoy a pipe of it.) He used to take me out trawling all night. When the nets were down he would while away the time by singing very slowly an interminable ballad with the refrain – which I thought ill-timed – ‘And the salt water was his grave’.”

In a letter dated 7th August 1911, Vaughan Williams wrote to Shaw:

“The man who sings well is William Hurr – ask him for “Lovely Joan” (otherwise “mounted on his milk white steed”) and “Loss of the London” and get some more!”

There is no indication that Shaw noted down any folk songs from the Hurrs and it was left to the specialists and enthusiasts Vaughan Williams and Butterworth to follow up William Hurr’s songs on a brief return visit to Southwold in December 1911, after their main visit on that occasion to the Diss area.

On Tuesday 25th October they revisited William & Robert Hurr, went on to Reydon to see a Mr Newby, then moved on to Filby, near Caister in Norfolk and finished up the following day at nearby Rollesby. This was a return visit for both men, as Vaughan Williams had collected a number of songs in 1908 and Butterworth had visited the same area with Francis Jekyll earlier in 1910.

Singing and Locations

Folk songs usually tell a story, and as such entertain an audience, whether in a pub, at a family party or on board a boat. In the days before recorded music, when people made their own entertainment to a large extent, and life was less crammed with information, even ballads of eight or ten verses were frequently memorised.

Many singers would also feature at least one sentimental song and one comic song in their repertoire, although these lighter-hearted items were not always noted down by the early folk song collectors, particularly as some were of relatively recent origin at the time, coming from the music hall and minstrel era. One Norfolk fisherman boasted that in a six-week trawling trip, he could sing two songs every evening without repeating himself. Sam Hurr, younger brother of the singing Hurrs, worked for skipper James Spence, who was described in an obituary in the Southwold Magazine in 1924 as being distinguished ‘not least by the inexhaustible selection of songs which cheered the passage home’. What a shame Butterworth and Vaughan Williams didn’t get to meet him too! The songs they noted down probably represent only a part of the singers’ repertoires, and they weren’t around for long enough to investigate further.

Where Vaughan Williams and Butterworth met up with the Hurrs is not known, certainly in other places it is known that they went into pubs. Given that they met on two consecutive days, it is possible that the first occasion was in a pub, followed up by a quieter session to check out details (in the case of William Hurr’s singing of Lovely Joan, Vaughan Williams wrote it out a second time). The Southwold Arms was a big pub for singing many years before this and also after it, and the White Horse would also have been a good bet for a singsong when in Charles Newby’s hands a dozen or so years before this date, but where the favourite singing pubs were in 1910 is not known. A newspaper report from 1899 indicates a serious rift between brothers William and Ben Hurr, when what was evidently a long-standing feud erupted into a violent argument on the beach, offending some lady visitors and ending up in court, so unless the brothers had made up their differences, it’s unlikely they would all have met in the pub for a friendly sing-song! Vaughan Williams and Butterworth both often noted the names of pubs where they collected songs, and there is no indication of pubs from them on the Southwold visit.

The singers and their songs

All three of the Hurrs were fishermen, from a large family going back generations in the town of Southwold. Their fortunes were mixed, their father William having suffered setbacks all through his life: the most traumatic perhaps being the sinking of his fishing punt the Susannah in 1893, with two of his youngest sons on board, followed only a month later by the death of his wife.

The Hurrs intermarried with other local families such as the Palmers and the Lowseys, and it was common practice to christen children with more than one forename, frequently with their mother’s maiden name as a middle name. Forenames were also passed on from generation to generation, and to avoid confusion, men in particular were often known by nicknames.

The period preceding the song collectors’ visit was one of change for the brothers; their father died in 1908, and by 1910 their financial situation was such that all three owned their own small fishing boats: William had the Vigilant, Robert the Boy Billy and Ben the Happy Thought. These were all longshore luggers, around 2 tons, which would have been used no more than a couple of miles offshore to catch herring, sprats, shrimps, sole, cod and mackerel in season, and moored on the beach (although the harbour had been rebuilt in 1907, it was mostly used by small coastal freighters and there were 120 open boats recorded as still working off the beach in that year). Happily for Vaughan Williams and Butterworth, bad weather prevented most small fishing boats from putting to sea during the period of their visit in 1910. According to the Halesworth Times on November 1st, ‘light fishing continued at Southwold on Saturday, and taking the week through, the results were far from satisfactory. Many boats either spoilt or lost whole fleets of nets during the earlier part of the week, and consequently several luggers had to remain in harbour over the weekend awaiting new nets.’

Links are given below to individual songs in the manuscripts of George Butterworth and Ralph Vaughan Williams, which have been digitised by the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Sometimes both men noted down the same song when working together, but I have only given one link for each song. Anyone interested in pursuing this aspect further needs to look into this in more detail than I have given here.

William Hurr (1843-1925)

William Watson Hurr, known as ‘Dubber’, was the eldest son of William and Maria Hurr, and like his younger brothers, was both born and buried in Southwold. In 1895 he married Matilda (née Adams) who was working as a servant to a solicitor in Southwold, and was a widow with two teenaged children from her first marriage to Joseph Adams, a private in the Royal Marines.

William Watson Hurr, known as ‘Dubber’, was the eldest son of William and Maria Hurr, and like his younger brothers, was both born and buried in Southwold. In 1895 he married Matilda (née Adams) who was working as a servant to a solicitor in Southwold, and was a widow with two teenaged children from her first marriage to Joseph Adams, a private in the Royal Marines.

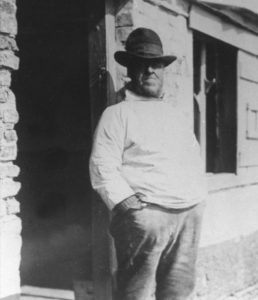

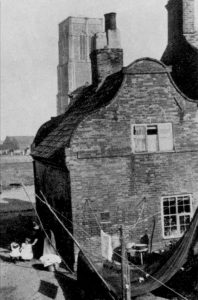

By 1901 the family were living in what is now the Southwold Museum, which was then divided into two tiny cottages later condemned as unfit for housing. In the photograph here, you can just make out Matilda with their children Susannah and Sam.

By 1912 however, William’s family were installed in a more spacious home at Caterer House, 39 Victoria Street, where Matilda was the landlady of holiday apartments, a line of business shared by at least two of her sisters-in-law. During the First World War, ‘Dubber’ showed the indomitable Hurr spirit by refusing to follow war-time regulations which banned night fishing, which apparently resulted in him being shot at and sustaining an injury to his arm. His son William Samuel Thomas (known as Sam) was one of the first not to follow in the family tradition of fishing, and after William’s death, his boat the Vigilant passed to his nephew, Ben’s son William Albert Benjamin – now the need for those nicknames becomes apparent!

By 1912 however, William’s family were installed in a more spacious home at Caterer House, 39 Victoria Street, where Matilda was the landlady of holiday apartments, a line of business shared by at least two of her sisters-in-law. During the First World War, ‘Dubber’ showed the indomitable Hurr spirit by refusing to follow war-time regulations which banned night fishing, which apparently resulted in him being shot at and sustaining an injury to his arm. His son William Samuel Thomas (known as Sam) was one of the first not to follow in the family tradition of fishing, and after William’s death, his boat the Vigilant passed to his nephew, Ben’s son William Albert Benjamin – now the need for those nicknames becomes apparent!

Half of the songs recorded from William Hurr relate to the sea. Vaughan Williams noted down only two verses of The Loss of the London, and some detective work was necessary to reconstruct the song for performance and publication. The Bold Princess Royal is a popular song up and down the east coast, indeed Vaughan Williams also noted down a version from Williams younger brother Robert the following day. In a small community, singers usually ‘owned’ a song, and this one probably belonged to William as the older brother. Robert would undoubtedly have known it through hearing William sing, but would not have sung it in public. Of the other songs, Lovely Joan is a classic folk ballad, whilst Three Jolly Butchers tells a tale of highway robbery and double-dealing first printed in the late seventeenth century. Again, detective work has been required to identify the fragments of When I Was Bound Apprentice: you could call the process musical archaeology!

Just recently (2022), I’ve found that George Butterworth also noted down the words to another song from William Hurr, Betsy of Yarmouth and Vaughan Williams noted down a melody for this, although it has been incorrectly titled in the catalogue as Kind Betsy Farmer.

Robert Hurr (1855-1934)

Robert Watson Hurr, fourth son of William and Maria, married to Elizabeth Stannard and father of six children, was also a fisherman, and in later years worked in partnership with his son William Walter Robert (known as Walter). After the Second World War, Walter co-owned the boat Daisy with Ben’s son: these appear to be the last two of the family to be working fishermen. After the First World War one of Robert’s five daughters, Annie, kept a pub, the Royal, in Victoria Street with her husband Arthur Brown. This was just across the road from Robert’s house, which was in turn just round the corner from his eldest brother William’s and five minutes’ walk from younger brother Ben’s.

Robert Watson Hurr, fourth son of William and Maria, married to Elizabeth Stannard and father of six children, was also a fisherman, and in later years worked in partnership with his son William Walter Robert (known as Walter). After the Second World War, Walter co-owned the boat Daisy with Ben’s son: these appear to be the last two of the family to be working fishermen. After the First World War one of Robert’s five daughters, Annie, kept a pub, the Royal, in Victoria Street with her husband Arthur Brown. This was just across the road from Robert’s house, which was in turn just round the corner from his eldest brother William’s and five minutes’ walk from younger brother Ben’s.

Robert was the only one in the family known to have played an instrument, and as such, would have been in demand at family gatherings and local parties. The only tune recorded from him is named The Liverpool Hornpipe in Vaughan William’s manuscript, although in fact it is nothing like the usual tune of that name and is actually a variant of what is perhaps the most widely-known hornpipe, Soldier’s Joy. Hornpipes were, and still are, commonly used for ‘stepping’: an informal, improvised form of tap dancing, usually danced solo and particularly popular amongst fishermen on the east coast. It is therefore extremely likely that Robert would have played for such dancing in the pubs and taprooms of Southwold. It is also likely that his repertoire included some other dance tunes, perhaps some schottisches, polkas or waltzes for couple dances, and also popular song tunes.

Robert’s song In London Town I was Bred and Born (also known as A Wild and Wicked Youth) is a ‘goodnight’ ballad: supposedly the last speech made by a prisoner before being hanged. Such songs were popular throughout the country, and if you were a Londoner, the actual hanging was an opportunity for an outing: Tyburn in London attracted huge crowds, which in turn drew numerous ballad-sellers and hawkers. Bold Princess Royal is one of the widely sung songs of coastal East Anglia, popular with all sea-faring sorts, whether sailors, fishermen or bargemen. A third song from Robert, noted as The Tiresome Wife by Vaughan Williams and On Monday Morning I Married A Wife by Butterworth has proved very difficult to identify, as no words were noted down at the time. The Royal George tells of the loss of a sailor at sea. There is some doubt as to whether it was Robert or William who sang this song – the only evidence being from Butterworth’s manuscripts, where he attributed it to Robert. It was one of the favourite songs in the community project we ran to revive these songs in 2003/4. However, it appears that Butterworth and Vaughan Williams were not so taken by it, as Butterworth commented “I don’t think we should publish this. It does not seem to me anything but a reminiscence of a quite late 18th century composed song.’

Ben Hurr (1860-1934)

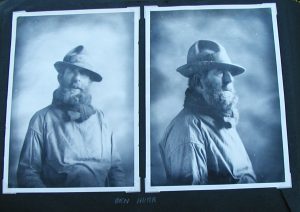

Benjamin Lowsey Hurr, the seventh of William and Maria’s eleven children who lived to adulthood, married Louisa Stannard and had one son. In the 1890s, along with brothers William and Robert, he was a member of the lifeboat crew. In the early twentieth century Ben and his family moved out of the small fishermen’s cottages in Victoria Street into one of the newer terraces in the north end of the town. These fabulous portraits may be “our” Ben Hurr, but it’s not possible to be 100% sure.

Benjamin Lowsey Hurr, the seventh of William and Maria’s eleven children who lived to adulthood, married Louisa Stannard and had one son. In the 1890s, along with brothers William and Robert, he was a member of the lifeboat crew. In the early twentieth century Ben and his family moved out of the small fishermen’s cottages in Victoria Street into one of the newer terraces in the north end of the town. These fabulous portraits may be “our” Ben Hurr, but it’s not possible to be 100% sure.

The Cobbler tells a story popular since at least Chaucerian days of a cuckolded husband, and is full of giggle-inducing phrases and motifs such as the adulterer hiding under the bed. Again Vaughan Williams noted no words to this song, perhaps thinking the humour rather low, but it would no doubt have gone down a storm in the company of other fishermen and mariners. The Isle of France (an early name for Mauritius) tells a sentimental tale of a shipwrecked convict on his way home after six years of exile being rescued by a coastguard and receiving a pardon from the Queen. Jones’s Ale, popularised in the late twentieth century folk revival, is a deceptive song, dating as it does from at least 1594. It seems possible that both he and his brother Robert knew this song, as Vaughan Williams attributes his version to Ben and Butterworth to Robert.

There was one more song collected in Southwold itself, which wasn’t attributed to any singer by either Vaughan Williams or Butterworth, unfortunately: It’s of a Rich Old Farmer. In the Book “Blyth Voices” which I wrote and researched in 2003, the contents page has mistakenly included this song under Ben Hurr’s name, and therefore there is a bogus attribution to him also in the VWML online catalogue.

Martha Keble / Cable (1829-1918)

On the first of their two day visit, Vaughan Williams and Butterworth went to the small village of Shadingfield, on the main road to Beccles. There Butterworth noted down the tune to one song from a ‘Mrs Keble aged 84’, and Vaughan Williams wrote down the words to a toast by Mr Keble. Records for Shadingfield in the early twentieth century show no-one by the name of Keble, although it is a common Suffolk name, but there was a Martha Cable living there in 1901, aged 70, widow of farm worker George Cable, and living with her was her unmarried son Frederick, then aged 33 (and they were at the same location in 1911). It seems more than likely that these are the people Vaughan Williams and Butterworth visited in 1910. It was evidently a somewhat disappointing trip, as the only song noted down from Mrs Keble was The Murder of Maria Marten, which Vaughan Williams had previously noted down in Kings Lynn in 1905, and which he left to Butterworth to note down on this occasion. The lyrics were well known, having been printed on a ballad sheet soon after the real event (sometimes known as the Red Barn Murder) in the 1820s: the songsheet and murder report sold over a million copies in the nineteenth century, and the story and ambiguous nature of the evidence inspired a stage melodrama which is still presented in repertory occasionally, followed by a film in 1935 starring Todd Slaughter and in the late twentieth century a television drama. The tune is a version of that used for the old ballad Dives and Lazarus which inspired Vaughan Williams to compose a piece for the 1939 World’s Fair in the USA.

On the first of their two day visit, Vaughan Williams and Butterworth went to the small village of Shadingfield, on the main road to Beccles. There Butterworth noted down the tune to one song from a ‘Mrs Keble aged 84’, and Vaughan Williams wrote down the words to a toast by Mr Keble. Records for Shadingfield in the early twentieth century show no-one by the name of Keble, although it is a common Suffolk name, but there was a Martha Cable living there in 1901, aged 70, widow of farm worker George Cable, and living with her was her unmarried son Frederick, then aged 33 (and they were at the same location in 1911). It seems more than likely that these are the people Vaughan Williams and Butterworth visited in 1910. It was evidently a somewhat disappointing trip, as the only song noted down from Mrs Keble was The Murder of Maria Marten, which Vaughan Williams had previously noted down in Kings Lynn in 1905, and which he left to Butterworth to note down on this occasion. The lyrics were well known, having been printed on a ballad sheet soon after the real event (sometimes known as the Red Barn Murder) in the 1820s: the songsheet and murder report sold over a million copies in the nineteenth century, and the story and ambiguous nature of the evidence inspired a stage melodrama which is still presented in repertory occasionally, followed by a film in 1935 starring Todd Slaughter and in the late twentieth century a television drama. The tune is a version of that used for the old ballad Dives and Lazarus which inspired Vaughan Williams to compose a piece for the 1939 World’s Fair in the USA.

Charles Newby (1830-1910)

On Tuesday 25th October Vaughan Williams and Butterworth cycled over to Reydon, to the Almshouses (pictured below) and noted two songs from a Mr. Newby. Charles Newby, then aged 79, was born in Sotherton but lived most of his life in Southwold. He kept the White Horse Inn at the Reydon end of the High Street for many years and was later a coal merchant when he lived at 13, Station Road, in the left hand house of a pair known as Gladstone Villas. He would have been one of the earliest inhabitants of these distinctive almshouses, which were built in an Arts and Crafts style in 1908, thanks to local benefactor Andrew Matthews. Inhabitants had to be over 65 years of age and to have lived in the town for at least 20 years.

Newby died just a few weeks after Vaughan Williams and Butterworth noted down two songs from him, Georgey, and Forty Miles. The first is a classic ballad, reputed to date from real events in 1594, and tells of a wife pleading (unsuccessfully) for the life of her husband who is about to be hanged. Forty Miles has a happier ending, with a chance meeting ending in marriage. It has a repeated line, so that, like Jones’s Ale, it would be a popular song to sing in places where the company would be in a mood to join in, perhaps even in the White Horse when Newby was landlord there.

Music-making did not stop after the song collectors’ visit of course, and what is known about it in the later twentieth century is published here, on the page Southwold in the later twentieth century. Interestingly, there was no overlap between the early 20th century repertoire as shown in Vaughan Williams and Butterworth’s collections and the songs collected in the later 20th century.

With thanks to: John Goldsmith, W.B. Hurr, Gary May, Southwold Museum, Southwold Sailors’ Reading Room, Andrew Jenkins, Jim Blythe, Trevor Ray, John Winter, Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (English Folk Dance & Song Society), Malcolm Taylor and many others who helped along the way.

Afterword

My research into Vaughan Williams and Butterworth’s folk song collecting in south Norfolk, in December 1911, was updated in 2019 and is now on this site here, and my work on Vaughan Williams’ visit to King’s Lynn in 1905 has ben updated in 2021 and is available here. Again, the information on the EATMT site is now superseded by the more recent versions published here.

Here’s the link to my 2021 talk ‘Up from the Sea’, again, on the Traditional Song Forum’s Youtube channel.

Here’s the link to my 2021 talk ‘Up from the Sea’, again, on the Traditional Song Forum’s Youtube channel.

© Katie Howson 2021